Art is Technology: When the Fascination Shivers

Jing Yi Teo

But it’s also easy to imagine a time when children would skid past robots like Temi to be captivated by a sparkling, shapeshifting hologram floating around like a robo-fairy from their wildest dreams. Technology is that which is not yet understood, says the venerable Silicon Valley investor Naval Ravikant. Fascination is always tinged with an aspect of incomprehensibility, the throbbing swell of an unknown substance. Even though the metaverse, blockchain, social media and artificial intelligence (AI) come to mind when most of us think of technology today, the largest and deepest technological investments are still deployed for military purposes. Uncovering — and even undoing — the crypticness that beholds most of the infrastructure and tools that are held in godly regard could perhaps rewire the sorts of knowledge and literacy we have about and around technology, if we were to inch closer to seeing it as something to be understood at all.

In the fields of anthropology and philosophy, there is a foundational definition of technology as an intrinsically human extension of the self1. In that sense, to obstruct our relation to technology from crossing over the realms of fascination to the sphere of cognisance would be a tremendous ode to human vanity. Is the creation of technology — particularly consumer technologies and new media showcases built for the “wow” factor — closer a planetary-scale catwalk?

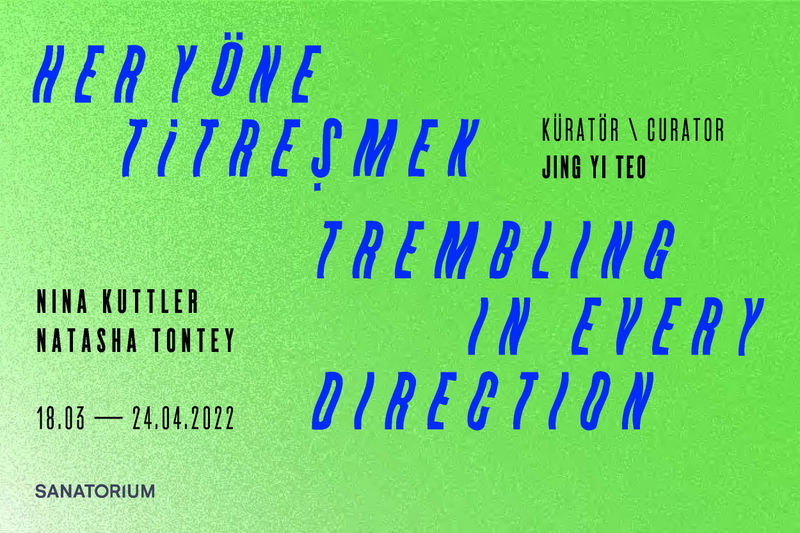

Trembling in Every Direction, the exhibition’s title, references Édouard Glissant, not because I had seen the documentary One World in Relation where Glissant said, “We understand the world better when we tremble with it, for the world trembles in every direction”, but because I had read the sentence quoted by Paul B. Preciado in his book An Apartment on Uranus. I admit this because I wish to point out the provenance of knowledge behind creative outputs, even in an instance as minute as my curation of this exhibition. Discoveries turn into inventions which are then building blocks for the next discoveries and inventions and ad infinitum2. What about the pieces in the stack which are proven wrong, as has happened in history time and time again? (An Apartment on Uranus is itself an escape to Uranus, now recognised as a planet but was dismissed as another star in prehistoric times no thanks to its dimness.) While discovery and disproving is the churning of the wheel for science, can we speak of technology at the tips of our fingers?

In contemporary times, a number of thinkers have theorised technology as indeed the tips of our fingers, extended. Ruha Benjamin and Beth Coleman has made the case for race itself as a technology designed to stratify and sanctify social injustice that is already internalised in the architecture of everyday life3. Their arguments go beyond the notion that racial injustice intersects with and is enabled by the design practices of Big Tech. Similarly, with this exhibition I am proposing to think of art not only at the intersection of technology — here there is no spotlight on new media art practices often at the centre of “art x tech” initiatives — but art as a technology, the stick which we stick into the soil for ants to crawl up towards us, so that we may each be closer to one another. The practices of participating artists Nina Kuttler and Natasha Tontey, both based on fiction as a method of speculative thinking, present their own personal ways of sensemaking of the world.

Kuttler’s research and practice anchors on the intention to blur the borders between mythology and science. A Ship to Sink Another Ship, titled after Leonardo Da Vinci’s abandoned sketches of submarines, are a series of sculptures modelled after early ideas and drawings of the most critical military technologies of all time, their sketched forms a far cry from what we understand of submarines today. Constructed in neon, an outdated material that evokes a nostalgic conflation of progress with technology, the sculptures refer to the era of submarines when humanity thought we could go anywhere and modify the world to our advantage without consequences. The Loudest Animal is a soundscape of a synthetic ecology where human and non-human entities coexist, extending the fraught relationship between submarines and the pistol shrimp into a fiction in deep-time. Kuttler’s work rests on the perspective — at once liberating and imperative — that if time exists so far into the future and into the past, histories might as well be fiction, and that there is agency in inventing and archiving parafictions4.

Tontey’s video works Wa’anak Witu Watu and The Epoch of Mapalucene features footages of indigenous Minahasan practices, which centre on the relationship that the Minahasan people, which Tontey descends from, has with stone, a geo-entity. Wa’anak Witu Watu includes a ritual where people charge their amulets’ energy in a neighbouring stone called ‘Watu Muntu Untu’. I ask Tontey if, then, she regards the ritual as a technology. She replies that she used to, but now prefers the concept of technē (from the Greek), or more commonly technique, which is non-universal and often the result of a series of rejection5. When the micro-local histories behind everyday tools and practices are respected through narration, there is also space for the altercation, and perhaps even the alteration, of the version of the truth that is accepted. In Wa’anak Witu Watu, Tontey reconfigures the societal position of the Goddess Kareema and her daughter Lumimuut, typically considered subordinate to Lumimuut’s son Toar, to a more glorified esteem, and in The Epoch of Mapalucene she speculates Mapalus, the Minahasan political system based on the stone’s significance in commoning resources as an alternative to the current system governing Indonesia.

In arguing for the importance of thinking about how technology has changed the concept of art Walter Benjamin illustrated that the concept of art enlarges to include new mediums, according to the current technological condition6. And while we continue to enlarge radius of things which we consider art, with all the resistance and theories that enlargement churns out, may we also lean towards the possibility that art is a technology, as the extension of ourselves which we deliberately instrumentalise to make sense of the world around us — the science, non-science and non-sense.

1 Among other theorists, this can be credited to Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media: The Extension of Man (1964; Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1994), and Bernard Stiegler, Technics and Time (1994, Galilée)

2 Packy McCormick, Compounding Crazy (Not Boring newsletter, August 2021, published via Substack)

3 Ruha Benjamin, Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code (Polity 2019)

4 Carrie Lambert-Beatty, Make Believe: Parafiction and Plausibility (October Magazine. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009)

5 Siegfried Zielinski, Deep Time of the Media: Toward an Archaeology of Hearing and Seeing by Technical Means (MIT Press, 2006)

6 Walter Benjamin, The Work of Art in the Age of technical Reproducability (1935)